Here is the thirteenth chapter of Taking Heart and Making Sense.

If you’re new here, you might like to read an intro article about the book. I also recommend listening to the book’s Introduction first. You can also find all previous chapters, in order, here.

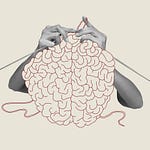

I consider this chapter one of the most important of the book. It builds on the concept of feeling as a sense of fit (chapter 10) and ideas about the development of feeling in early life (chapter 12). To recap, experience and understanding reinforce each other and scaffold on previous experiences, particularly experiences from early childhood. In this chapter I propose that our feeling experience is metaphorically structured (metaphor was explained in chapter 2) but in a way that is much more individualised than in language use (the area with which we normally associate metaphor).

If the notion of experience as structured seems confusing, it might be easier to think of as ways we recognise situations, including how we sense ourselves in those situations. Our feeling experiences rely on recognition, which is mainly unconscious but emerges into our conscious awareness as a sense of fit. That feeling can then be further differentiated into other feeling experiences. The idea that we recognise situations based on past experience fits well with Lisa Feldman Barrett’s view of emotion, but aligning the process of recognition with metaphor and describing it as unique to individuals is new.

I’m not sure how this sounds to readers, or even precisely where these ideas fall on the spectrum between obscure and obvious! I’ve spent so many years reflecting on them, not simply as disembodied ideas but as real ways I’ve engaged with my own personal life experience. I’ve long thought that the best way to explain some of the key concepts of the book is by illustration through real examples. But I’m a fairly private person and not willing to lay out the details of my difficulties, particularly if that reflects badly on people I care about. Even so, I did rummage through some memories and managed to dig up an example from my own life, which I’ll recount. (The childhood experience I describe involved strong feelings at the time, but both that and the later experience were fairly innocuous overall.)

My parents were both first-generation migrants, from Denmark to Australia. They didn’t exactly choose to migrate. Both travelled here on work visas freely handed out by the Australian government to encourage new workers in the late 1960s. Then, as often happens, life had its own plans: they met each other here and (after various twists and turns) they both stayed. Married for just a few years, they divorced when I was three. When I was five years old my mother took my older sister and I back to Denmark. We spent a wonderful Christmas in Copenhagen, and I met my relatives for the first time.

My childhood memories are generally pretty vague, but some snippets from that trip are brightly etched in my memory. Our holiday had a magical, fairytale quality. Twinkling Christmas lights lined the snowy city streets. Thick icicles dangled from the eaves outside our windows. An enormous fir tree with real candles lit up my grandparents’ apartment. The golden yellow of their apartment walls reflected my warm feeling of family. After the quietness of my small family and a divorce, the party of ten or so family members at our Christmas Eve dinner felt like a joyous throng. I felt something new, the deep, primal sense of family connection: these were my people.

In Denmark, Christmas Eve is the main event, with a lavish roast dinner, dessert, singing and presents to follow. My sister and I were the only children there so we were given the important task of handing out all the presents, one by one, in the very slow, civilised fashion of that time. As a young child, that felt to me like an exceptional privilege, to be given a special role among these new folk! The centre of attention no less! The reason I remember it, though, is because I messed it up. I had two uncles and at some point I picked up a gift from one to the other. Somehow I wasn’t quite clear which uncle was which, and I gave it to the wrong one. Perhaps I was a bit muddled because I didn’t understand Danish. I must’ve looked confused, because everyone laughed. There was nothing in it, no malice or desire to humiliate: they probably all thought it was cute. But already fairly shy, I was absolutely mortified, so embarrassed because I so much wanted them to like me. Of course I couldn’t verbalise any of this, and that’s the only moment I remember. My big chance to impress them, gone awry.

Fast forward a little over thirty years to my father’s funeral. By that time I could actually speak Danish, having spent a gap year there and become fairly fluent. My father had lived the rest of his life in Australia, so we had arranged to livestream the ceremony for his relatives in Denmark. I had written his eulogy, but thought my step-brother would do a better job of delivering it. Still, we’d agreed I would offer a short welcome in Danish to the family overseas. I was a little nervous as I hardly ever spoke Danish, but it felt important; I wanted to include the family watching from afar. It felt like a special role.

But once I began speaking, my pride in the language and my desire to welcome fizzled into a state more anxious than I was expecting. When I welcomed my father’s nephews, my cousins, by name I somehow mixed up their names. I made new names! Instead of Karsten and Lars, I said Larsten and Kars. I immediately knew I’d done it but had to keep going, and I got through the rest of my danish sentences well enough. Still, I was mortified. No one else who was there in person understood my Danish, but they did know the names of my cousins, so that was the bit they all noticed. Even worse, I imagined my relatives in Denmark laughing at my odd mistake.

I probably mentioned this slip up to my friends and family on the day. I seem to remember saying “I can’t believe I said that” quite a few times. I tried to make light of it, knowing rationally that it didn’t matter at all. Everyone would forget. But inside, a little part of me just cringed. I felt embarrassed.

I hope the example of these two scenarios conveys something of the curious nature of the past in the present. Imagine me stepping up to address everyone at the funeral. Suddenly my heart was racing and I couldn’t quite concentrate; I knew I didn’t like public speaking but I had also looked forward to offering this. Of course I had many reasons to feel anxious or uncomfortable in the emotional setting of a funeral; the childhood scenario I described was only one influence. But see how the structure of the past meets the present: a family situation in which I have an unusually high emotional investment, the unfamiliarity of being the centre of attention, wanting to impress my relatives, and in particular, a special role. Perhaps even a much more general feeling of wanting to belong, to connect with my people. And somehow I make the situation repeat. I make literally the same mistake as my five-year-old self (I mix up the names of two male relatives). And it is completely unexpected, but I create the same feeling: a mix of embarrassment and shame.

What’s interesting to me is that both my present behaviour and experience echo the past, even though I don’t know it at the time. And it isn’t a general categorising of a situation (I don’t like public speaking and therefore get anxious): it’s present in the details (down to the details of the mistake itself). Somehow I create my experience anew. I unconsciously recognise how the specific situation goes; I anticipate it and I make it happen. Of course this is a strong example, an initial one-off situation that I remember as being painful. Much of our feeling emerges from more repetitive, ongoing situations and interactions, and most of them we don’t explicitly remember.

By the time adult life rolls around we might simply notice themes in our interactions, in our trials and tribulations. We might wonder why we respond in certain ways to pressure at work, why we seem to attract the same characters as boyfriends or why a small issue comes up repeatedly with different friends. We do project our previous understanding to make sense of present situations, and those projections might be of very similar situations (of a category) or really quite different (in the style of metaphor). Not only that, people come along to fit into our projections; we don’t imagine them. That’s just how it happens. The past colours the present as it makes it possible. We are not usually conscious of the influence of the past, but our feeling (as an understanding) includes it. Unlike agreed upon words, whose meaning is shared, this feeling process is unique to individuals. Certain very specific details in particular situations bring behaviours forward, and, when they are important enough, feelings.

That’s what I mean by unique, individual metaphors.

To be clear, before writing this I had actually never considered the memories of these two situations together. I’d all but forgotten them both. Initially I was actually trying to remember other situations in which I’ve been unusually nervous but which didn’t really make sense to me, times when I’ve felt a combination of not understanding what people are saying, wanting to belong and being afraid of looking stupid. They might all bring the structure of that initial situation forward in some way. But it was only in the exercise of writing this that I noticed the similarity of the mistake itself. I’d never considered those details before! I even found it a little amusing! It confirmed something I’ve believed for a long time now (albeit cautiously), that once you look, the details of experience really are surprising. That structuring, or relatedness, is a kind of synchronicity, indicating a genuine interconnectedness that is even more surprising.

Quick overview:

This chapter begins by reiterating that behaviour emerges as whole acts, at the level of the whole body, a different level from that of neural patterns. Feeling as the sense of fit is the inner aspect of these whole acts in relation. This is different from Barrett’s view that the brain predicts or categorises situations and then instructs the body.

I argue that behavioural responses and feeling involve the recognition of details of past situations, interpreted in relation to present circumstances. These details from the past (as memory that is present in functioning), need not be relevant or causal. Thus, rather than a process of categorisation, feeling is structured more similarly to metaphor in language: we project across domains, even at times across situations that may have very little in common. This makes individual feeling experiences highly consistent but unique; the details of individuals’ past history and present time situations are unique. We are all positioned differently, repetitively taking up familiar positions in situations while positioning others, to generate stable experience of the world and of ourselves.

Share this post