Here is the twelfth chapter of Taking Heart and Making Sense.

If you’re new here, you might like to read an intro article about the book. I also recommend listening to the book’s Introduction first. You can also find all previous chapters, in order, here.

To return to some of the foundational ideas of my book, one aspect of a process metaphysics, set within the orientation of speculative naturalism, which I find especially useful is it’s directive that we keep a clear eye on the observable, natural world, while we attempt to describe and understand our human experience. For me, this focus supports rigorous, systematic inquiry, a kind of speculating within limits; we don’t begin our theory with ideas about a divine realm or even a human soul, but rather with nature.

Nonetheless, in the past couple of years I have had to face the untimely deaths of people I love, and have found myself searching beyond the limits of this life. Questions about life after death have taken on a new significance and my interest in religion and spirituality renewed. I remain guided by trust in my own, embodied experience above all else, but my personal beliefs about what might happen after we die, or even before we are born, are open to change. Yet even within that broader searching I’ve found that my basic sense of how human life develops in the natural world still holds. There are important ways in which this human life, in the physical world, seems to be fairly contained. Even if we do bring our personality in with us (as a reincarnated soul or through the process of our genetic lineage, or somehow both), we are also highly formed by the forces around us; the familial, societal, religious and cultural environments that surround us, as well as the natural world from which we grow.

A few months ago I listened to a talk given by a Buddhist monk, Ajahn Brahm, who resides in Australia. He relayed an intriguing anecdote about a family who had sought his advice about reincarnation. This family had a highly unusual experience with their newborn baby. One night, at only two or three weeks old, the two parents both clearly heard their newborn say “Good night Peter” to his sibling, a toddler three or four years of age. He said it twice, so they certainly heard it, and his voice was clear and adult, and he knew the name of his brother. Obviously, this would be a surprising or even life-changing experience for those parents (indeed, they were not Buddhists but sought Ajahn Brahm out to try to make sense of their experience). This story, both mundane and mystical, speaks of realms beyond the world of our everyday awareness. Yet a less obvious, but still remarkable point is that it didn’t happen again: their baby spoke on just that one occasion. He then went on to learn to speak at the usual age of young children.

This story (which I hear in good faith and with an open mind) offers an indication of reincarnation, but it demonstrates something else that seems profoundly relevant: there are no short cuts. We absolutely must go through the stages of human development, whether or not we are souls, and whether here for the first and only, or the five-hundredth time. Within this natural world, we gradually incarnate, or become ourselves, whether entering from a spirit realm or simply through our ancestral lineage, from that equally mysterious separating and recombining of proteins, within cellular dynamics and through unfathomable numbers of generations.

In the first stages of our lives we come to recognise others within an ongoing, interactive process that literally forms our boundaries, our sense of self. Experience organises our perceptions, which are not initially separate from our feelings. We incrementally master bodily movement in space, but we also learn to navigate the world through the dawning perception of ourselves in relation to others; all of this experience forms our sense of fit and is the basis of our inner life.

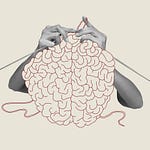

This chapter attempts to describe some of the processes by which this early experience is organised, as feeling and to become the sense of self and world. I draw on work by the philosopher Martha Nussbaum, who puts forward a neo-Stoic view of emotions. Her view of how feeling develops in early life resonates very well with the inner aspect, the holistic sense of fit within a semi-autonomous system. Our sense of self begins in interaction with others and as we map the world, forming as our own history forms; none of these can be separated in early life. Nussbaum is influenced by psychoanalysis but with an important emphasis that is at times missing in that field, on the infant’s need for comfort and reassurance as a basic need; this is a feeling-based need, distinct from other biologically-based needs.

Many readers might be at least somewhat familiar with attachment theory, that how we were cared for and responded to as infants can directly affect how we experience and behave in adult relationships. We act in certain ways in unconscious attempts to bring forth behaviour from a significant other that will adjust our own feelings (such as to reestablish a sense of safety following an episode of anxiety). For me, the more I understand these dynamics, the more interesting they become, particularly because we can describe these whole complexes as beliefs about causes as well as feelings. We do things in certain ways (such as inadvertently manipulate others by demanding or withdrawing attention) because in some very real sense we believe this is the only way to get what we need. Yet for the insecurely attached, the results are often disappointing, negatively reinforcing beliefs about unmet needs (because the behaviours that were adaptive for an infant may not work in adult relationships). Such patterns can be very difficult to identify, because they literally are our feelings, our sense of what to do or how things should be.

As with other theories covered in the book, infant development is an enormous area of scholarship from which I attempt to explain a few key points. But I hope the way I draw on Nussbaum’s work and formulate infant development, in the context of the previous chapters, offers something new. It sets up some important claims about feeling that will carry through to the end of the book. These early experiences influence more than our significant relationships; in the case of pervasive difficulty, neglect or trauma in early life, they may set up our basic perceptions about the world (such as that the world is unwelcoming or unfriendly) and our sense of our own capacity to do almost anything (such as to look after ourselves or learn something new).

Moreover, understanding infant development strongly supports the curious notion that feeling is a present experiencing but profoundly repetitive of the past, that many of the ways we feel might be learnt in interactions we can’t remember but that crop up constantly in adult life. This is where I believe it is truly worth understanding these dynamics of human life, even if it can be confronting to see where we behave unconsciously because it simply feels like who we are. Identifying our patterns offers genuine possibilities for change, in this world and in this life (which together set the limits for most of our experiences), for our possibilities to reflect on those experiences and for the wisdom we might develop as a result.

Quick overview:

This chapter begins by aligning the sense of fit with Eugene Gendlin’s concept of the felt sense, reiterating the difference between emotion and feeling. I then discuss Martha Nussbaum’s account of infant development within her theory of emotion. Her view is amenable to the description of the self as a semi-autonomous system, simultaneously developing real boundaries and inner experience through interaction with others, particularly primary caregivers.

As the self develops through what Nussbaum terms the ambivalence crisis, early interactions give rise to feeling states that can be thought of as beliefs; they are modes of understanding based on repetitive activities that could have been different. Referring back to Bourdieu’s notion of habitus, I propose that we each develop a unique, individual habitus. The sense of self and beliefs about the world are heavily influenced by the details of early interactions.

Share this post