Here is the eleventh chapter of Taking Heart and Making Sense.

If you’re new here, you might like to read an intro article about the book. I also recommend listening to the book’s Introduction first. You can also find all previous chapters, in order, here.

Crimson rosellas are a bright, lively species of parrot, abundant where I live in south-eastern Australia. I love hearing them around my garden and as they fly through the valley our house overlooks. I often watch them when they land in the eucalypts nearby, calling out to others further away, hidden from my view. Rosellas have a broad repertoire of notes, whistles and squeaks, but when a lone bird calls out to another in the distance, it is usually a rhythmic bleat, like a soft bell: “boop boop”. I hear it as an inquiry and a greeting at the same time. If the inquiry is answered, a paired call and response often follows, a back and forth with distinct timing. The same rhythm is often noticeable in the subtle movements of the rosella I can see, who stretches out a little with interest and anticipation while calling out, then sits back to listen and receive an answer. Of course I don’t know what these signals mean for them, but these interactions have an unhurried and receptive quality, an exchange of presence somehow: “I’m here”, “I’m here too”. It’s very sweet, and sometimes I wonder if our human conversations aren’t just a jazzed up version of that: I’m here, I’m here too, I’m here, and so on! If it’s true that our consciousness is based on feeling, as a sense of fit, that might not be as silly as it sounds. Or at least it might illuminate something important about our motivations to connect with each other.

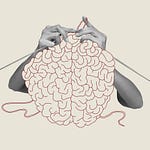

In the previous chapter I described the sense of fit as the inner aspect of our acting in the world, with that behaviour understood as fairly automatic (and in that sense nonconscious) but nonetheless complex. Fitting in the world requires that we entrain with and attune to all sorts of phenomena, not least other people. Our inner rhythms entrain to the rhythms of the world; to days, moons and seasons. As infants we entrain to our mothers and caregivers, as they attune to us, in the dance of daily life. As adults we constantly attempt to attune to others, to meet their interactional and attentional needs, as well as our own. This chapter explores how we do that nonconsciously, how our behaviour arises both from and with the body, but is also structured by the social and cultural, in our interactions with others. Our lives are literally made possible by our participation in all sorts of patterned interactions that we need not ever have learnt consciously, but have simply become used to over time.

One concept that stands out when we observe interactions is rhythm. Even within the simple bird calls I mentioned, the interaction itself, the back and forth, is held together by the rhythm; the notes and pauses are precise, and if they are too long, the interaction ends. Eliot Chapple (a little-known anthropologist whose work I discuss in this chapter) emphasises rhythm in his understanding of human biology in the context of culture. According to him, rhythm is an important feature of our interactions. We need only think of attentional shifts in conversation: we feel comfortable when the rhythm of the back and forth suits us, but if the pause is too long or too short we just feel off. We feel unheard when someone jumps in too early or awkward in long silences; we might try to end the interaction or even become anxious. Chapple suggests that we have interactional needs, linked to our biological rhythms and that these are unique to individuals. According to him, we are always trying to synchronise with others, and we often do, but not for long. Our motivation for all sorts of activities and interactions is to synchronise. His book, Culture and Biological Man: Explanations in Behavioural Anthropology, was published in 1970, and was in some respects ahead of its time; synchrony seems very similar to the contemporary psychological concepts of self-regulation and co-regulation.

In the second half of the chapter, I follow Chapple’s view with a discussion of sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, who has a somewhat different view of our patterned, nonconscious behaviour. Interestingly, Bourdieu created a name for the set of structures which we internalise and through which our behaviour arises: habitus. Habitus describes both a person’s dynamic, lived experience and an unconscious, interpretive structure. But Bourdieu is not so interested in the feeling or experience of individuals; he is more concerned with how class structures propogate themselves through our nonconscious behaviour. He suggests that we are driven by a desire for recognition, or cultural capital, which allows individuals to belong to groups or classes, and whole classes to dominate others.

To me, this seems partly true, yet I suspect that our need for recognition is much deeper. Extending Chapple’s idea of synchrony, recognition seems to me to be fundamental. Our ongoing search for recognition calls out to the paradox of our existence, that we are both separate and interconnected at the same time, ephemeral individuals in this human experience. We might seek recognition, through synchrony, simply to reassure ourselves: we are here and others are here. Curiously, this fleeting state might be where we feel the most stable, deeply with ourselves and the world at the same time, mutually cocreated and continually becoming, unhurried and receptive.

Quick overview:

This chapter explores nonconscious behaviour, in particular how social and cultural patterns organise human behaviour and interactions in ways of which we are usually unaware. I draw upon the work of anthropologist Eliot Chapple, who links biological and interactional needs with the notion of cultural sequences; all three rely on rhythm and timing. Chapple suggests that individuals have unique, biological rhythms, which also set their needs for interaction with others. From the moment of our birth, these internal rhythms prompt us to interact, in attempts to synchronise with others. Culturally patterned activities provide the means to do this.

I then discuss sociologist Pierre Bourdieu’s view of human behaviour as determined by social structures, particularly class. Bourdieu theorises the behaviour of individuals through the concept of habitus as both internalised structure and dynamic, lived experience. While Bourdieu is more focused on how class systems reproduce themselves, Chapple is more interested in how individuals attempt to meet their interactional needs. For Bourdieu our motivation is to seek recognition as a kind of status, understood as cultural capital, while Chapple emphasises our attempts to synchronise. I argue that we need to move beyond both of their views by understanding recognition as a deep human need for connection that reassures us of our very existence.

Share this post