Here is the tenth chapter of Taking Heart and Making Sense.

If you’re new here, you might like to read an intro article about the book. I also recommend listening to the book’s Introduction first. You can also find all previous chapters, in order, here.

Last summer, my partner and I went snorkelling in a marine national park in Port Phillip Bay, along the shores of which the city of Melbourne sprawls. Being alongside a major city, this large and relatively shallow bay is not exactly pristine, but we noticed that innovative replanting in the past few years had left the snorkelling spot noticeably more covered in vegetation. We spent an hour meandering among seagrass, kelp and rocks, and were quite surprised to see healthy numbers of multiple kinds of rather large fish; morwong, juvenile snapper and more. Wading out of the water towards the beach afterwards, chatting about our encounters, we exclaimed at almost the same time, “It’s like they know they’re in a marine park!”

Of course neither of us thought this was literally true, but we’d both noticed the same thing: many of these larger fish seemed totally unperturbed by our presence. They were positively noncholant as we swam close to and among them, not hiding or darting away, as we were more used to fish doing in other places. We might infer from their behaviour that these particular fish had never had reason to fear humans or other large predators. To be more precise, their behaviour demonstrated that they didn’t register our presence as a threat, suggesting that they didn’t preempt any potential harm from us and had no memory of being threatened by creatures like us. They sensed that they were safe.

The notion of feeling as a sense of fit is simply the way I imagine they might feel, or be conscious. It describes their felt sense of being able to go along doing their thing, to continue moving or exploring, swimming this way or that according to some inner urge or rhythm. Some of these fish did appear a little interested in us: some were certainly looking at us and a couple hung around quite close by. Perhaps that interest, within a sense of fit, simply feels like a push or curiosity to swim a little closer, an openness to an unfolding situation.

The feeling itself doesn’t sound very complicated; it isn’t meant to be. It describes the basic way any organism might simultaneously have a sense of itself and a sense of a situation, including any action a situation requires. We should remember that even this level of consciousness, which might sound simple, does seem to require a complex system capable of complex interactions, including nonconscious decision making. At the same time, we can fairly easily imagine the sense of fit as a holistic feeling, sensed inwardly, that fluctuates according to shifting needs and changes, which are constantly arising inside and outside the organism. The more refined the organism’s capacity to sense the inside and outside environments, the more differentiated the sense of fit becomes.

The concept of sense of fit is based on ideas already put forward in previous chapters: that organisms are always harmonising levels inside and outside themselves, and that most change is contained within semi-autonomous systems. Our conscious experience arises from both all that inward activity (or physiology, which includes memory) and our need to harmonise outwardly (or behaviour and interaction). We might identify the sense of fit in ourselves as feelings such as aliveness, safety, familiarity and recognition, or simply an openness to continue or a felt need to stop or shift.

If we were to observe the opposite behaviour to that described, say a fish suddenly changing direction and accelerating hastily away, we might imagine a strong push from inside, a sudden tension and rapid release as the movement unfolds. This doesn’t require a clear emotion such as fear. That push to escape from danger might feel like a sense of strong effort and the right response, rather than a feeling of threat, particularly if the escape route is fairly clear. For much simpler organisms the sense of fit might feature the feeling of aliveness more strongly, simply the buzz of inner functioning. Perhaps jellyfish (who have neural nets rather than brains and nervous systems) mainly feel their own digestion when nothing much else is going on! But even these animals have many different kinds of receptors, for light, movement, etc., and might experience holistic but shifting orientations, a very basic sense of fit.

In ourselves, we do many (if not most) day-to-day activities fairly automatically. We simply have a underlying sense that the action fits the situation, even if we don’t usually pay attention to that feeling. Yet, even beyond the mundane (or at least repeated) activities that make our lives possible, what turns us towards a new activity or even a new life path is often the subtle sense that something needs to change. We sometimes sense that something isn’t right long before we can articulate what that is. And while children might have difficulty noticing and naming their inner experience, they can be very clear about whether or not something feels right or ok. The sense of fit is feeling and understanding at the same time. Even if it is within a simpler, child’s view of the world, the sense of fit is there and is a meaningful expression and experience for that child in that moment.

The sense of fit is the basis of experience and it is inherently meaningful. The concept helps us to understand that meaning is immanent in nature, rather than something imposed by humans and from the outside.

Quick overview:

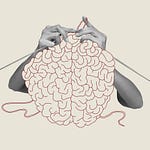

In this chapter I put forward the idea that the most basic form of consciousness is feeling. That feeling is a holistic, inner sensing, which I term the sense of fit. The sense of fit arises as the inner aspect or perspective of an organism, understood as a semi-autonomous system engaged in complex forms of behaviour and nonconscious deliberation. The term encapsulates the fundamental sense of self-in-relation, the meaningful interpretations and responses that harmonise inner and outer levels, experienced as feeling.

I then explore descriptions of the sense of fit, most basically as the openness to continue or the need to adjust. As humans and according to situations, we might experience the sense of fit as feelings of recognition, familiarity, safety, ease and aliveness. Sense of fit is both holistic and fluctuating, and shifts between being more inwardly and outwardly entrained. As Susanne Langer suggests, this inner sensing might begin evolutionarily with organisms experiencing the highest inner level of their own functioning. It might become more differentiated as new levels emerge within the system, and more refined modes of sensing an environment become possible.

Share this post