Here is the final chapter of Taking Heart and Making Sense. This week I have included the whole text, as well as my recording of it, to bookend with the text of the Introduction.

I’ll take a short break and then continue writing and posting new work fortnightly. My orientation might shift a little, becoming less academic and more exploratory. At the moment I feel drawn to some deeper reflecting on my own experience, but within topics that still connect to the themes of my book. That being said, I’m also looking forward to reading more in process philosophy, theoretical biology, neuroscience, feeling and embodiment, and bringing new ideas into my writing.

I saw a couple of scarlet robins on my walks this week, such sweet creatures and a sign of new beginnings. I hope you enjoy the last chapter!

Conclusion

To return to the title of this book, taking heart encourages us to understand and accept that feeling is unique and important; this in itself is an act of kindness towards ourselves. Making sense acknowledges that feeling is always an understanding; it is meaningful and reasonable in a way we can discover even when our experience seems inappropriate, exaggerated or just plain wrong. Within a broader social perspective, making sense suggests that we can find a way of understanding the position of human life in relation to nature, defined as all the processes and relations that form the world as we know it, which can help us to connect our situated knowledge of the world with our sense of meaning and value. Thus, the project of understanding human feeling within a theory of nature (in this case speculative naturalism) addresses the inward, personal nature of our experience but also recognises the fundamental relatedness of experience, with each other and all else. This provides the background for beginning to understand causal connections, our positioning in relation to all kinds of processes; to the manifold intricate, interwoven interactions, of stabilities that take form and change. While the goal of this book has been to develop a theory of feeling, this goal implies a broader social intention, that we might collectively take heart in relation to the monumental, existential issues humanity currently faces and the changes we must make. These are fundamentally issues of our own survival and flourishing, and our dependence upon stable and thriving natural systems and environments.

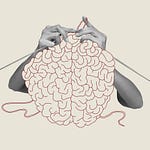

In terms of human experience, I have tried to describe just how much of our behaviour is automatic and nonconscious and that this is simply a part of being human, a kind of prerequisite for all the things we are able to do and to experience. I have also tried to put forward a clear and convincing argument about the need for stable experience; it is a matter of survival. This idea of stable experience makes an important link to those processes that already transcend divisions of body and brain —homeostasis and interoception—while preserving feeling as a holistic, emergent, and therefore creative level, one that each of us is uniquely within. Seeing this connection to, but separateness from, lower level physiological processes can in turn help us to understand how working from within our experience is not separate from the whole, living, physiological body, as human beings have long discovered in the healing potential of practices such as body-focused meditations, dance and movement, and even supporting and consoling each other with physical contact.

Even so, human beings go to great lengths, consciously and unconsciously, to avoid their own feeling experiences. Again, this can be vital for the maintenance of stable experience, always in the context of maintaining consistent relations with other people; we need to view this aspect of our humanness with compassion and understanding. At the deepest level, stable experience reassures us that we exist and that the world is as we believe it to be. While it is straightforward to understand why people become afraid and avoid situations that might result in physical harm or death, it is less obvious that many human behaviours aim to avoid experiences that might bring overwhelming feeling experiences, even temporary dissolution of the sense of self. Shame is perhaps the paradigmatic experience here, although phobias are another example, and the most extreme manifestation might be psychosis. Even more obscure is the fact that people often maintain painful, ambivalent or even destructive positions to maintain stability, which is not an indictment of human nature, but evidence of the strong coupling required for a self to emerge, of the protectiveness of consciousness in relation to difficult and overwhelming feelings such as despair and hopelessness, as well as shame and fear.

Yet understanding that present feeling so strongly bears the mark of the past means that we can become more open and curious towards our own experience, when we feel safe enough to do so. Here is where the physical body and experience are most obviously perspectives on the one process, of the self over time. When feeling is allowed into conscious experience (when we do not endlessly adjust ourselves and situations to avoid it) we become able to notice the natural direction of the system as a whole, from the inside, as feeling, towards internal resolutions that bring about openness, acceptance and compassion, those experiences that we must value, nurture and work towards as the evolutionary possibility present in the experience of being human. These tendencies, if supported and practiced, offer us a way to face the difficulties of life, the pain of loss and death, and to openly witness the staggering, wondrous reality that we are even here. This in no way suggests that opening to our suffering or facing our losses, our mistakes, or our flaws is easy. This opening must be encouraged and cultivated and requires courage, persistence and strength.

Understanding feeling in the way I have described it through this book does not mean that we should only attend to feeling, even if in quiet moments this is a valuable strategy. Rather, understanding feeling as emerging from lower level processes in the context of higher level processes—this between character of feeling—means that we give more space to feeling as we also observe what we are doing, including what we are thinking and what is going on around us.

This levels approach, thoroughly justified by hierarchy theory, is somewhat evident in burgeoning therapies such as dialectical behavioural therapy, which bridges cognitive behavioural therapy and mindfulness-based techniques. It includes exploration and acceptance of feeling but also efforts towards cognitive and behavioural change, while acknowledging the role of safety through the therapeutic relationship. us, the strategy of observing and accepting feeling is central, but the levels of action and explicit understanding, as well as interactional levels, in relationships, are all addressed.

When we see experience in relation to the highly entrained yet always somewhat tenuous physiological stability of which it is the inner aspect, in the context of the nearly unfathomable degree of order developed through millions of years of evolution, the necessity for stable experience seems more obvious. So much change is contained within the human being as a semi-autonomous system that our ideas about how we might change our experience, the highest, inner emergent level of complexity, become more modest and incremental but no less profound. When we work with the way things actually are, understanding the processes of the natural world from which we emerge and of which we are a part, we can approach the notion of changing our experience with much more patience and forbearance. When we let go of the idea that we should quickly transform our experience into something wholly different—to feel constantly happy, to never suffer, to recover spontaneously from an illness—then we open up to a different kind of change, developing subtlety within our own feeling experience and the physical and physiological changes this can bring. We might then experience moments of sublime attunement in our meetings with the world: sudden empathy for a stranger, delight playing with a child, a breathtaking silent encounter with a wild creature, or simply love for those who have unintentionally hurt us. Such moments do not make us immune to other realities of our human history—aggression, greed, humiliation, mistrust—but we become more flexible and resilient in our own experience. We can hold these realities differently.

The term unique, individual metaphors is meant to convey the betweenness of all our realities, our individual and collective experiences. Interactions at all levels—from the most simple encounters of a transaction with a shopkeeper, cooking dinner with a friend, or even saying goodnight to a loved one, to the more large scale and complicated of a government considering recommendations and passing legislation, the recovery of a community from a natural disaster, the emergence of the zeitgeist of a particular time—are formed of and in turn form stable, repeating processes that have identifiable structures. They exist and are actual but the ways we know and participate in them are from our own perspectives. Whatever we feel is, along with our history, a genuine understanding of and response to that which is actually occurring, albeit at a more generalised level than the more precise characterisations of language. As we participate in processes we also create them, but we only have a sense of how to create them because we have done or seen something similar before. If the most fundamental yet unfathomable reality is change that is cause of itself, and the most basic way that we can characterise anything from our human perspective is as processes formed in relation (knowable from the inside as experience and from the outside as any relation we identify) then when we change from within, when we pause or wait or completely stop our adjustments in behaviour and language and observe our experience such that we, in time, change our patterns, we effect actual change, however small in relation to the cosmos, or significant in relation to someone with whom we regularly interact. We form a different relation to that person, or group or even higher level social process. We literally make new positions for all other processes, even if those positions are not taken up or do not come to fruition. While the view I have developed in this book is in many respects similar to some forms of psychotherapy, on this point it is very different, as a result of the underlying metaphysical foundation. The extension of this metaphysical orientation requires a great deal more explanation than is possible here, but we can generally state that for interactions to arise requires people to have a relation to the situation that fits the relations of others, even if those relations are very different. And while this view must be explored with extreme care and sensitivity, it does create a space for observing the events and interactions around oneself as occurring in relation, although certainly not a simple causal relation that makes us responsible for what happens to us.

The embedded relatedness of the self as a process over time, in principle to all else, also means that we can at least consider less usual feeling experiences, including those that people often attribute to the rather nebulous term spiritual. While most of us are highly contained (in that we are influenced by our past experience such that creativity happens in small increments) creating more inner harmony over time, which brings the self into more present relations, potentially means that we can extend our perception of relatedness through our feeling experience. Here we would not then contact other realities but simply subtler realities, for instance a subtle sense of living or being that relates us to all forms of life. This is, after all, our ancient history and is in an important sense actually within each of us, literally in our functioning.

Of course in everyday human life our reflections on feeling tend to be much more mundane. Feeling obviously emerges from all the processes we can observe from the outside. These include physiological rhythms and entrainments going on in and outside of the body, arising as cycles of hunger, tiredness, desire and aging, and whatever habits we engage and challenges and stressors we regularly experience. This can explain something important about simulation. While simulation is no doubt also a useful strategy for self-regulation (in the way that Barrett describes) it is an activity, akin to behaviour, by which we create conditions to transcend those feelings that are more strongly coupled to physiological changes and cycles. We might make decisions over many days or weeks, or even longer, such that we have sensed into the scenarios of possible outcomes many times, from the perspective of many states, and we then develop an overall sense of what is best to do, not by explicitly remembering all our simulations and their contexts (was I tired, was I down, was I open?) but by building up a feeling sense that eventually crosses a threshold: yes, I should act this way. This is simply a wise way to live, understanding ourselves, our foibles and our biological reality but doing what we can to creatively adjust. It supports the idea that being able to sense the inner body and identify various states is conducive to greater stability and flourishing throughout life and that accurately sensing the inner body is a useful skill, one that is not a given but can be learnt and refined over time.

If we want to work with our feeling experience in relation to other people but feel stuck or don’t know how, we can try observing our positioning, especially when it seems familiar. Often we will want to do this when we feel thwarted in some way. In such cases, the usual response is to place blame somewhere, to perceive the situation in terms of simple and linear relations of cause and effect. There is nothing inherently wrong in doing this, but it is always a limited perspective because linear relations never describe whole situations and how they have come about. Thus, one act that we can take is to suspend blame, not because we condone the harmful behaviour of others, but because we take a more open stance towards a situation and by doing so we literally change our relation to it, even if only minimally; we create space for something else to happen. This should not be taken to imply that a situation will spontaneously resolve into something better or easier; we might experience more difficult feelings or circumstances. But if we can hold them in a steady space then eventually they will change and we will sometimes find the present or repeating situation or relationship less acute or troubling when it arises again. Very possibly we will eventually change our relation to the person or circumstance enough that it doesn’t arise again in the same way. When we do this we create a new, actual relation to another person and we offer that person the possibility of taking up this altered position. This is why the dynamics of forgiveness are so important. Forgiveness frees others from deflecting or defending against our blame even if we remain clear that we disagree with and do not condone the person’s actions or even intent. The very act of forgiving can mean the difference between guilt and shame for those we forgive and generate the potential for creative atonement that can help people to heal and flourish, including perpetrators. Again, this is difficult to imagine but relies on the foundation of process/relation, that relations have the same ontological status as processes: they are not derivatives of processes but are equally real.

At the same time, because individuals are uniquely positioned, we can never really know how conscious or unconscious the behaviours of others are and therefore how much their experience relates to present situations; it is difficult enough to discover this in ourselves, let alone in others. We all have varying degrees of dissociation and denial in relation to the intricacies of the circumstances of our lives. Most people will have had realisations of how they really felt about some event, which is better expressed as really were influenced by or positioned in relation to an event, well after it has passed. Such realisations might even occur many years later, for instance as the repercussions of trauma finally reveal themselves later in life or when a person feels safe enough to open up to it. Again, we needn’t see these dynamics as entirely problematic. They are how we protect ourselves and fit with each other so that we may continue living. However, these dynamics do suggest that no one else can tell us how we really feel or are positioned; we must discover this within ourselves and attempt to do so with care. Bringing our unique, individual metaphors to light can mean challenging the very structures that hold us together.

Thus, in relation to the infractions of others, we should not forgive falsely, even with good intention. We can only observe and listen to feeling as well as explicitly deciding to try to forgive, that someone deserves our forgiveness. If we do override our feeling, such as with alternate explanations, we might be able to more or less absorb or hold the disharmony inwardly, at lower levels. But if disharmony persists we might find that impulse emerging in some other situation or we might even become unwell from ongoing discordant lower-level processes; the overall system is less whole. In such cases we have not changed our overall relation to the situation. To do so a person might need to work through very difficult, painful or even frightening feelings, perhaps through a whole lifetime. If the process remains incomplete for that person that is just how it is. The point is not that people deny their own feelings of hurt or betrayal or worse, but that we have something to work towards, to free ourselves and others if we possibly can. These are the extensions of the foundation of change and our differentiations of process/relation, from the way I have framed them in relation to all the theories discussed. They are meant as suggestions for ways we might observe and work with our experience and, importantly, observe the outcome. An interesting aspect of the underlying metaphysics is that we do not need to let someone know we have changed—we may never see them again—but that changing ourselves inwardly simultaneously alters relations; that is what relations are. The causal import for others exists even when they don’t explicitly know it.

Suspending judgement about the cause of a situation or even just observing that a situation involves circumstances that have been encountered before, potentially very specific circumstances, at the personal level in no way suggests that we should not hold others accountable for their actions in present-time situations. Rather, it is another level of description of a situation that attempts to work with the unfolding of change at a deeper level. If anything, exploring this other description improves our rational, collective deliberations about how to organise groups and societies and how to deal with transgressions, because it allows us to respond more to present situations and less from our individuated history. Feeling will still be there; potentially it will be clearer such that we act with greater conviction, but it might be altered in the sense that we take strong action but without malice or extend compassion even as we set a boundary. These high standards of engagement with others and situations require an inner harmony that results from attention and practice. They are highly unusual but they are possible and they are aligned with the view of human beings as separate and individuated as well as interconnected.

When we work creatively with our own experience, finding ways to open within limits, to change while we remain stable and to offer those inner changes towards greater harmony when we interact with others, we engage the highest potential for human beings at this point in our evolution. We are in and of the natural world, formed by and forming countless activities and interactions, but we are unique because we can consciously reflect on our own experience. We can discover how experience is created and how best to steer it, and when we do this within ourselves, we alter the very fabric of the relations of existence. The self becomes more highly attuned to present circumstances. We can meet others more openly and intimately and act with greater kindness and fairness. These expressions of our humanness help us, as with the resolution of the ambivalence crisis, to accept and live within the paradox that life is tenuous, frightening and painful but that we are immensely privileged to be alive, participating in the lives of other people and other living beings. Accepting and appreciating this cannot but extend to the natural world in which we live. We can become more concerned beyond ourselves, to find ways to live and to engage with living beings and non-living phenomena that encourage the stability necessary for the continuity of life itself, in all its creative manifestations—the subtle interplay—and the trust and safety that supports human beings to flourish within it. If we can understand and value each other, we can develop a finer appreciation of the unique but finite processes of our lives and the vast processes of evolution that have made our lives possible, as change becomes conscious of itself.

Share this post